29th AUGUST 2015 YAMI TWIN SISTER OF YAM

Yami - Twin Sister of Yama

यमि

According to the Rig Veda, Yami is the twin sister of Yama. Their mother is Saranyu (who is the daughter of Tvashta, the artisan God) and their father is Vivasvant (associated with the sun). She is extremely fond of her brother.

There is a dialogue [R.V.10.10] between her and Yama, where she expresses her love for him and invites him to her bed. He rejects her advances, saying that "The Gods are always watching us, and shall punish the sinful." She is heart-broken.

In another story, Yama finds the way to the land of his fathers. He voluntarily choses death, and becomes the first man to die. Yami could not stop crying, so great was her grief. When the Gods tried to console her, she replied, "How can I not mourn, for today is the day of my brother's death!". To cure her, the Gods created night. From then on, night follows day and the cycle of time began. This story is cited as an example of the power of time as the healer of grief.

Yama

The Robert Beer Blog

Blog History

Yama and Yami

Posted by Robert Beer on 4/8/2014 1:13:45 AM

YAMA and YAMI

The Rig-Veda, meaning ‘praises of knowledge’, is the first of the Four Vedas or sacred Indo-Aryan scriptures of the ancient Indian tradition, which may possibly date back to earlier than 1900 BC. In the verses of this most primordial of all written scriptural texts the origins of many of the great Vedic gods are given, including that of Yama and Yami, who were the first two mortal humans to be born upon this world. As primordial twins they were born from the union of Surya, the Sun God, and his wife Sanjna, whose name means ‘Conscience’. The original implied meaning of the male Vedic name Yama was ‘twin’, but the term later came to mean ‘restrainer’, or more precisely ‘the restrained one’. And the female name Yami commonly relates to a ‘sister’, who later was personified as Yamuna, one of the great river-goddesses of India.

As twins Yama and Yami were conceived and delivered from Sanjna’s womb, and as in the legend of Adam and Eve from the Book of Genesis, they were both likewise born into a garden of earthly delights. In this natural paradise time seemed to stand still, it was always daytime and the season was always spring-like, the sun always shone while the moon and stars remained hidden behind its brilliant light. The fragrant flowers never wilted, the trees always bore an abundance of delicious fruits, the birds sang sweetly, and all the creatures of the earth lived in harmony with one another. And likewise did Yama and Yami live in harmony with one another, and as they grew so did their love for each other blossom. But the restrained sentiments of Yama were different from that of his sister Yami, who sought to unite with her twin brother in an incestuous relationship.

The text of the Rig-Veda is quite explicit on her propositions, where Yami says: “My desire for Yama overwhelms me, to lie with him on the same common couch. I will yield myself as a wife would to her husband. Let us hasten to unite, like the two wheels of a wagon.”

To which Yama replies: “The sentinels of the gods, which wander around us, never stand still, never close their eyes. Associate yourself with someone other than me, and exert yourselves in union, like the two wheels of a wagon. The succeeding times will come when brothers and sisters will perform acts that are unmeet for kinsfolk. But not so for me, O fair one! Seek another husband other than me, and make your arm a pillow for your consort.”

Yami then says: “ Is he a brother whose sister has no lord? Is she a sister when destruction comes? Overcome by love these words I utter, come near me and hold me in your close embrace.”

To which Yama replies: “I will not entwine my arms around your body. They call it a sin when one draws near to his sister. Enjoy your pleasure with someone other than me; for your brother, auspicious one, has no such desire.”

“Alas, Yama, you are weak,” says Yami, “In you I find no trace of heart or spirit. Some other female will embrace you as a creeper clings to a tree.”

“Then find another to embrace you Yami,” replies Yama. “Let another enfold you, even as a creeper circles a tree. Win his heart and let him win your fancy, and he shall form with you a blessed alliance.”

Her advances having thus been shunned, Yami wanders away from her brother, but when she returns later she finds Yama lying still beneath a tree, as if he were asleep. She softly calls his name and gently shakes him, but Yama does not respond. She calls louder and shakes him harder, but Yama still does not stir. Then she notices that Yama’s body is cold and that he does not breathe, and suddenly she realizes that Yama is no longer alive and that she is now completely alone in this world. This revelation is terrible, Yami’s heart has been broken and her grief knows no bounds. Her tears well up and pour from her eyes in a torrent that soon becomes a river (the Yamuna), which began to flood the earth. And because the sun always shines and the day appears to be everlasting, Yami’s great sorrow is likewise eternal and can never be abated, and the world resounds with her soul’s dreadful lamentations that endlessly echo from the pit of her deepest despair.

In vain did the gods seek to comfort Yami, as they assumed visible forms and tried to physically console her, yet the only words she would say were: “But Yama just died today! Yama died today!” Time after time they tried to reason with her about the transient nature of existence, of how all that is born must inevitably die, of how all sorrows and memories will ultimately grow weaker, but always the only words she repeated were: “But Yama only just died today! Yama died today!”

After taking counsel together the gods finally realized that Yami’s sorrow perpetually existed simply because she herself existed in a perpetual interval of time. For within this earthly paradise it was always today, there was no yesterday and no tomorrow. And for her grief to even begin to alleviate the gods reasoned that they must first bring an equal interval of night into being, for only then could today end and tomorrow truly begin. So the great Vedic gods of the earth and sky used their creative powers to bring night into existence by causing the sun to sink below the western horizon and to later rise again above the eastern horizon. During this interval of darkness the moon and stars made their first appearance against the velvet-black vault of the sky, causing the birds and creatures of the air and earth to seek rest and fall into the deep abyss of sleep, and along with these creatures Yami also slept for the first time. She awoke as the dawn sky was breaking with the awareness that Yama had died before the onset of night, and she said to herself: “Why, Yama must have died yesterday!” And when the next sequence of dusk and dawn had come to pass, she said: “Why, Yama died the day before yesterday!”

As the days passed and the seasons began to make their presence known, Yami’s grief slowly began to ease with the diurnal passage of time, for there were now nocturnal intervals of sleep that divided her days, when oblivion came to vanquish the pain of her brother’s death and the memories of their cherished yet brief existence together. And although her grief remained while her waking memories persisted, Yami was the first mortal to experience the true nature of human existence, and she became wise through the acceptance of her suffering.

Yama’s destiny, however, was to follow a different path. For having been the first man ever to be born, he was also the first man ever to have died, and as the Rig-Veda clearly reveals he was also the first human being to: “Find the way home, which cannot be taken away.” For through dying fearlessly as the ‘restrained one’, with all of his senses and moral values under control, Yama left this world without any karmic imprint or sin. Because of this Yama become the first human being or ‘forefather’ to discover the ineffable secrets of life, death, and the cosmic laws that govern existence. Through experiencing death as a portal to immortality he attained the divine status of a god in his own right, becoming the ‘Lord of Death’ or ‘Lord of the Dead’, with the auxiliary title of Dharmaraja, meaning the ‘King of Dharma’ or righteousness.

"Depart by the former paths by which our forefathers have departed. There shall you behold the two monarchs Yama and Varuna rejoicing in the Svadha." (RV:10.14.7)

"Be united with the forefathers, with Yama, and with the fulfillment of your wishes in the highest heaven. Discarding iniquity, return to your abode, and unite yourself to a luminous body." (RV: 10.14.8)

In Buddhist cosmology Yama’s heaven is ranked as the third of the six heavens of the ‘desire realm’, which are listed as: (1) The Heaven of the Four Great Kings: (2) Indra’s Heaven of the ‘Thirty-three’ Gods (Skt. trayastrimsa): (3) the Heaven of Yama: (4) The ‘Joyful’ Heaven of Tushita: (5) The Heaven of the Gods that delight in Creation: (6) The Heaven of Gods with dominion over others creations.

In the epic Indian poetry of the Mahabharata the heaven of Yama is described as:

“Being neither too hot nor too cold. Where life is without sorrow, where age does not bring frailty, tiredness or bad feelings. Where there is no hunger or thirst, where everything that one would seek is found there. Where the fruits are delicious, the flowers fragrant, the waters refreshing and comforting; where beautiful maidens dance to the tunes of celestial musicians, and where laughter blends with the strains of heavenly music."

"The Pavilion of Yama was fashioned by the divine carpenter Tvashtri, it shines like burnished gold with a radiance equal to the sun. Here the attendants of the Lord of Dharma measure out the allotted days of mortals. Great sages (rishis) and ancestors wait upon and adore Yama, who is the ‘King of the Fathers’ (pitris). Sanctified by holiness, their shining bodies are clothed in swan-white garments, and adorned with jeweled bracelets, golden earrings, exquisite flower garlands and alluring perfumes, which make that building eternally pleasant and supremely blessed. Here hundreds of thousands of saintly beings worship Yama, the illustrious King of the Pitris.”

CHITRAGUPTA

The Vedic scriptures relate that the souls of all human beings are judged after death according to the free and ordained deeds of body, speech and mind they have performed during the course of their lives. As the Lord of the Dead, Yama Dharmaraja was assigned the task of presiding over these afterlife judgments with the help of his attendants or messengers, who are known as yamdhutis. But the sheer number of souls that appeared before him would often overwhelm Yama, he could sometimes be confused as to their identity and then pass the wrong judgment upon them. When Brahma became aware of this he commanded Yama to keep more accurate records of the deeds of all beings, to which Yama replied: “My Lord, how can I alone keep records of the deeds of all beings that are born into the eighty-four hundred thousand different kinds of wombs throughout the three worlds?”

Upon hearing this Brahma entered into a prolonged state of deep meditation, and when he eventually opened his eyes he saw before him the figure of a man holding a reed pen and an ink-pot in his two hands. “You have been created from my body (kaya),” declared Brahma: “And henceforth your offspring shall be known as kayasthas. You were conceived within my mind (chitra) and in secrecy (gupta), and therefore you will be known as Chitragupta.”

Both Yama and his messengers, and Chitragupta as the ‘keeper of secrets’, frequently appear in the near-death experiences of present day Hindus, Jains and Sikhs. Where Chitragupta as a scribe or record-keeper appears holding the book or account of each individual’s human life, and sure enough there some mistakes in Yama’s judgment which Chitragupta has to rectify by sending some individuals back to live out there allotted span on Earth. In this respect they equate with the reluctant individuals of our western realm who are told to return by a deceased relative or a being of light during their life review.

Text by Robert Beer

The Rig-Veda, meaning ‘praises of knowledge’, is the first of the Four Vedas or sacred Indo-Aryan scriptures of the ancient Indian tradition, which may possibly date back to earlier than 1900 BC. In the verses of this most primordial of all written scriptural texts the origins of many of the great Vedic gods are given, including that of Yama and Yami, who were the first two mortal humans to be born upon this world. As primordial twins they were born from the union of Surya, the Sun God, and his wife Sanjna, whose name means ‘Conscience’. The original implied meaning of the male Vedic name Yama was ‘twin’, but the term later came to mean ‘restrainer’, or more precisely ‘the restrained one’. And the female name Yami commonly relates to a ‘sister’, who later was personified as Yamuna, one of the great river-goddesses of India.

As twins Yama and Yami were conceived and delivered from Sanjna’s womb, and as in the legend of Adam and Eve from the Book of Genesis, they were both likewise born into a garden of earthly delights. In this natural paradise time seemed to stand still, it was always daytime and the season was always spring-like, the sun always shone while the moon and stars remained hidden behind its brilliant light. The fragrant flowers never wilted, the trees always bore an abundance of delicious fruits, the birds sang sweetly, and all the creatures of the earth lived in harmony with one another. And likewise did Yama and Yami live in harmony with one another, and as they grew so did their love for each other blossom. But the restrained sentiments of Yama were different from that of his sister Yami, who sought to unite with her twin brother in an incestuous relationship.

The text of the Rig-Veda is quite explicit on her propositions, where Yami says: “My desire for Yama overwhelms me, to lie with him on the same common couch. I will yield myself as a wife would to her husband. Let us hasten to unite, like the two wheels of a wagon.”

To which Yama replies: “The sentinels of the gods, which wander around us, never stand still, never close their eyes. Associate yourself with someone other than me, and exert yourselves in union, like the two wheels of a wagon. The succeeding times will come when brothers and sisters will perform acts that are unmeet for kinsfolk. But not so for me, O fair one! Seek another husband other than me, and make your arm a pillow for your consort.”

Yami then says: “ Is he a brother whose sister has no lord? Is she a sister when destruction comes? Overcome by love these words I utter, come near me and hold me in your close embrace.”

To which Yama replies: “I will not entwine my arms around your body. They call it a sin when one draws near to his sister. Enjoy your pleasure with someone other than me; for your brother, auspicious one, has no such desire.”

“Alas, Yama, you are weak,” says Yami, “In you I find no trace of heart or spirit. Some other female will embrace you as a creeper clings to a tree.”

“Then find another to embrace you Yami,” replies Yama. “Let another enfold you, even as a creeper circles a tree. Win his heart and let him win your fancy, and he shall form with you a blessed alliance.”

Her advances having thus been shunned, Yami wanders away from her brother, but when she returns later she finds Yama lying still beneath a tree, as if he were asleep. She softly calls his name and gently shakes him, but Yama does not respond. She calls louder and shakes him harder, but Yama still does not stir. Then she notices that Yama’s body is cold and that he does not breathe, and suddenly she realizes that Yama is no longer alive and that she is now completely alone in this world. This revelation is terrible, Yami’s heart has been broken and her grief knows no bounds. Her tears well up and pour from her eyes in a torrent that soon becomes a river (the Yamuna), which began to flood the earth. And because the sun always shines and the day appears to be everlasting, Yami’s great sorrow is likewise eternal and can never be abated, and the world resounds with her soul’s dreadful lamentations that endlessly echo from the pit of her deepest despair.

In vain did the gods seek to comfort Yami, as they assumed visible forms and tried to physically console her, yet the only words she would say were: “But Yama just died today! Yama died today!” Time after time they tried to reason with her about the transient nature of existence, of how all that is born must inevitably die, of how all sorrows and memories will ultimately grow weaker, but always the only words she repeated were: “But Yama only just died today! Yama died today!”

After taking counsel together the gods finally realized that Yami’s sorrow perpetually existed simply because she herself existed in a perpetual interval of time. For within this earthly paradise it was always today, there was no yesterday and no tomorrow. And for her grief to even begin to alleviate the gods reasoned that they must first bring an equal interval of night into being, for only then could today end and tomorrow truly begin. So the great Vedic gods of the earth and sky used their creative powers to bring night into existence by causing the sun to sink below the western horizon and to later rise again above the eastern horizon. During this interval of darkness the moon and stars made their first appearance against the velvet-black vault of the sky, causing the birds and creatures of the air and earth to seek rest and fall into the deep abyss of sleep, and along with these creatures Yami also slept for the first time. She awoke as the dawn sky was breaking with the awareness that Yama had died before the onset of night, and she said to herself: “Why, Yama must have died yesterday!” And when the next sequence of dusk and dawn had come to pass, she said: “Why, Yama died the day before yesterday!”

As the days passed and the seasons began to make their presence known, Yami’s grief slowly began to ease with the diurnal passage of time, for there were now nocturnal intervals of sleep that divided her days, when oblivion came to vanquish the pain of her brother’s death and the memories of their cherished yet brief existence together. And although her grief remained while her waking memories persisted, Yami was the first mortal to experience the true nature of human existence, and she became wise through the acceptance of her suffering.

Yama’s destiny, however, was to follow a different path. For having been the first man ever to be born, he was also the first man ever to have died, and as the Rig-Veda clearly reveals he was also the first human being to: “Find the way home, which cannot be taken away.” For through dying fearlessly as the ‘restrained one’, with all of his senses and moral values under control, Yama left this world without any karmic imprint or sin. Because of this Yama become the first human being or ‘forefather’ to discover the ineffable secrets of life, death, and the cosmic laws that govern existence. Through experiencing death as a portal to immortality he attained the divine status of a god in his own right, becoming the ‘Lord of Death’ or ‘Lord of the Dead’, with the auxiliary title of Dharmaraja, meaning the ‘King of Dharma’ or righteousness.

"Depart by the former paths by which our forefathers have departed. There shall you behold the two monarchs Yama and Varuna rejoicing in the Svadha." (RV:10.14.7)

"Be united with the forefathers, with Yama, and with the fulfillment of your wishes in the highest heaven. Discarding iniquity, return to your abode, and unite yourself to a luminous body." (RV: 10.14.8)

In Buddhist cosmology Yama’s heaven is ranked as the third of the six heavens of the ‘desire realm’, which are listed as: (1) The Heaven of the Four Great Kings: (2) Indra’s Heaven of the ‘Thirty-three’ Gods (Skt. trayastrimsa): (3) the Heaven of Yama: (4) The ‘Joyful’ Heaven of Tushita: (5) The Heaven of the Gods that delight in Creation: (6) The Heaven of Gods with dominion over others creations.

In the epic Indian poetry of the Mahabharata the heaven of Yama is described as:

“Being neither too hot nor too cold. Where life is without sorrow, where age does not bring frailty, tiredness or bad feelings. Where there is no hunger or thirst, where everything that one would seek is found there. Where the fruits are delicious, the flowers fragrant, the waters refreshing and comforting; where beautiful maidens dance to the tunes of celestial musicians, and where laughter blends with the strains of heavenly music."

"The Pavilion of Yama was fashioned by the divine carpenter Tvashtri, it shines like burnished gold with a radiance equal to the sun. Here the attendants of the Lord of Dharma measure out the allotted days of mortals. Great sages (rishis) and ancestors wait upon and adore Yama, who is the ‘King of the Fathers’ (pitris). Sanctified by holiness, their shining bodies are clothed in swan-white garments, and adorned with jeweled bracelets, golden earrings, exquisite flower garlands and alluring perfumes, which make that building eternally pleasant and supremely blessed. Here hundreds of thousands of saintly beings worship Yama, the illustrious King of the Pitris.”

CHITRAGUPTA

The Vedic scriptures relate that the souls of all human beings are judged after death according to the free and ordained deeds of body, speech and mind they have performed during the course of their lives. As the Lord of the Dead, Yama Dharmaraja was assigned the task of presiding over these afterlife judgments with the help of his attendants or messengers, who are known as yamdhutis. But the sheer number of souls that appeared before him would often overwhelm Yama, he could sometimes be confused as to their identity and then pass the wrong judgment upon them. When Brahma became aware of this he commanded Yama to keep more accurate records of the deeds of all beings, to which Yama replied: “My Lord, how can I alone keep records of the deeds of all beings that are born into the eighty-four hundred thousand different kinds of wombs throughout the three worlds?”

Upon hearing this Brahma entered into a prolonged state of deep meditation, and when he eventually opened his eyes he saw before him the figure of a man holding a reed pen and an ink-pot in his two hands. “You have been created from my body (kaya),” declared Brahma: “And henceforth your offspring shall be known as kayasthas. You were conceived within my mind (chitra) and in secrecy (gupta), and therefore you will be known as Chitragupta.”

Both Yama and his messengers, and Chitragupta as the ‘keeper of secrets’, frequently appear in the near-death experiences of present day Hindus, Jains and Sikhs. Where Chitragupta as a scribe or record-keeper appears holding the book or account of each individual’s human life, and sure enough there some mistakes in Yama’s judgment which Chitragupta has to rectify by sending some individuals back to live out there allotted span on Earth. In this respect they equate with the reluctant individuals of our western realm who are told to return by a deceased relative or a being of light during their life review.

Text by Robert Beer

supposed to catch hold of his victims and a mace in the other, which represents the weapon of punishment.

supposed to catch hold of his victims and a mace in the other, which represents the weapon of punishment. As being the judge of the dead, he is said to hold a court, in which he is the presiding officer. He has another small god to assist him, who is called CHITRAGUPTA. Chitragupta is supposed to keep an account of the actions of men. If the actions of the deceased in his lifetime have been wicked, he is sent to suffer in a particular part of hell, while a man with noble deeds is sent to a part of heaven.

As being the judge of the dead, he is said to hold a court, in which he is the presiding officer. He has another small god to assist him, who is called CHITRAGUPTA. Chitragupta is supposed to keep an account of the actions of men. If the actions of the deceased in his lifetime have been wicked, he is sent to suffer in a particular part of hell, while a man with noble deeds is sent to a part of heaven. Yama is regent of the south quarter and as such is called DAKSHINASAPATI. His abode is named as YAMALYA on the south side of the earth and has an interesting legend around it. This account is taken from the Mahabharata. The narration is that after Brahma had created the three worlds, viz. EARTH, HEAVEN and PATAL (i.e., subterranean region), he recollected that a place for judgment and punishment of the wicked was wanting. He therefore asked the architect Vishwakarma to prepare a suitable place for this purpose. Vishwakarma prepared a magnificent palace and opposite its south door he created four pits to punish the wicked. Three other doors were reserved for the entrance of the good so that they might not see the place of punishment when they went to be judged. Brahma named this palace SANJEEVANI. Brahma ordered the architect to form a vast trench around and fill it with water, which came to be called VAITAMEE. Brahma next ordered Agni (the fire god) to enter this river so that the water might boil. After the death each person is obliged to swim across this Vaitamee river, which gives harmless passage to good souls but the evil ones have to suffer torments and pangs while crossing this river’s boiling water.

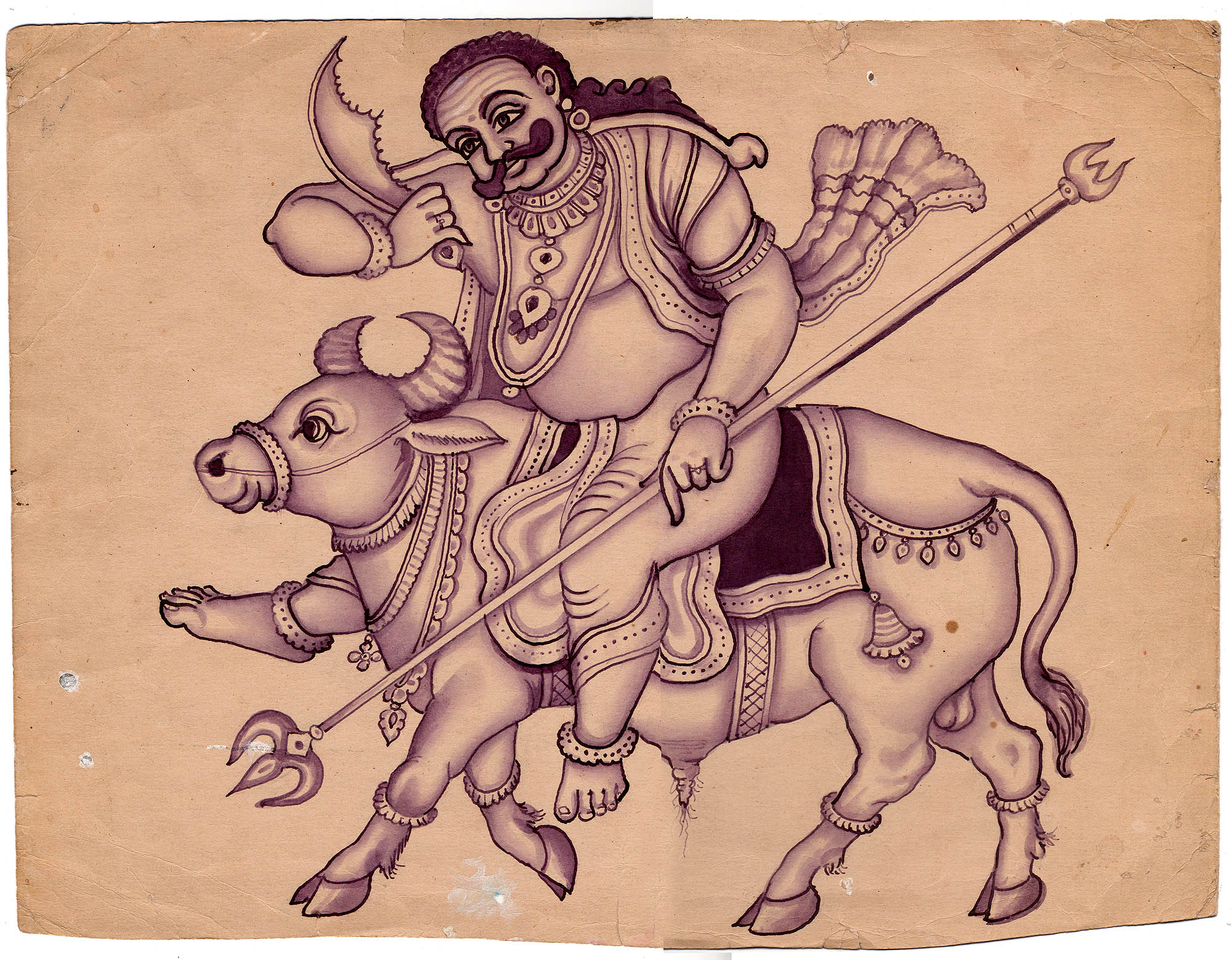

Yama is regent of the south quarter and as such is called DAKSHINASAPATI. His abode is named as YAMALYA on the south side of the earth and has an interesting legend around it. This account is taken from the Mahabharata. The narration is that after Brahma had created the three worlds, viz. EARTH, HEAVEN and PATAL (i.e., subterranean region), he recollected that a place for judgment and punishment of the wicked was wanting. He therefore asked the architect Vishwakarma to prepare a suitable place for this purpose. Vishwakarma prepared a magnificent palace and opposite its south door he created four pits to punish the wicked. Three other doors were reserved for the entrance of the good so that they might not see the place of punishment when they went to be judged. Brahma named this palace SANJEEVANI. Brahma ordered the architect to form a vast trench around and fill it with water, which came to be called VAITAMEE. Brahma next ordered Agni (the fire god) to enter this river so that the water might boil. After the death each person is obliged to swim across this Vaitamee river, which gives harmless passage to good souls but the evil ones have to suffer torments and pangs while crossing this river’s boiling water. To the virtuous and to the sinner Yama appears in different forms. To the virtuous he appears to be like Vishnu. He has four arms, a dark complexion and lotus shaped eyes. His face is charming and he wears a resplendent smile. In the case of the wicked, he is seen with limbs appearing three hundred leagues long. His eyes are deep wells. His lips are thin, the color of smoke, fierce. He roars like the ocean of destruction. His hairs are gigantic reeds, his crown a burning flame. The breath from his wide nostrils blows off the forest fires. He has long teeth. His nails are like winnowing baskets. Stick in hand; clad in skins, he has a frowning brow.

To the virtuous and to the sinner Yama appears in different forms. To the virtuous he appears to be like Vishnu. He has four arms, a dark complexion and lotus shaped eyes. His face is charming and he wears a resplendent smile. In the case of the wicked, he is seen with limbs appearing three hundred leagues long. His eyes are deep wells. His lips are thin, the color of smoke, fierce. He roars like the ocean of destruction. His hairs are gigantic reeds, his crown a burning flame. The breath from his wide nostrils blows off the forest fires. He has long teeth. His nails are like winnowing baskets. Stick in hand; clad in skins, he has a frowning brow.

No comments:

Post a Comment